4

After having read the terms of the treaty that Lobengula was so anxious to reverse, and having conferred with Fairburn as to the circumstances that led to such a debacle, three days later I sat down with the king, drafting a letter that we were going to mail to the British commandant based in Fort Victoria, a small military town that the British had set up on the margins of Lobengula's empire. To me, there was no doubt what Lobengula was asking me to do was something that had been attempted before but without any success. And I would not have bothered with it had I not seen that agreeing to help the king would in turn cause my requests to be treated with greater favour by the court.

Within a couple of hours of sitting down and confabbing in that dusty secret room of the king's, I had Lobengula's treaty objections properly worded in the best English I could write.

"Sign here," I pointed to the little space on the page that I had reserved for his signature.

A bottle of ink sat on the table, ready. Lobengula pulled the bottle closer to him and peered into it. His nostrils flared as the odor of the ink reached him. I wondered what was going through his mind—whether by the action of his nose he was just reacting to the ink's chemicals, or if subconsciously he was regretting the fact that his illiteracy had done him a lot of bad, recalling the day he, by a similar liquid, signed away a good chunk of his authority.

"I have my own writing instruments, but I rarely use them," Lobengula amplified as he took the pen I offered him.

He dipped the pen into the bottle, then withdrew it.

"Right there," I pointed my finger at the blank space opposite his name.

The king drew an 'X' on the space. For a man who'd never gone to school, the 'X' seemed reasonably straight.

After waiting for the ink to dry, I folded the letter and gave it to him. "Now you can send it."

"Good job, Jacob, I cherish what you have done." Lobengula wobbled to his feet; and I, too, stood up.

We stepped outside into the air, which today felt humid and smelt of rain. Not far from his house, two warriors on horseback, whom he'd already summoned, waited to be dispatched. Lobengula handed the letter to one of them—who shoved it into the bag he carried. Who said no mailing system existed whatsoever in Africa? I imagined these two horsemen as a verdant sprouting of a post-office system, one which with some refinement could become very efficient. And my education efforts would contribute greatly towards that. Life was going to change here.

"You may go," the king ordered the warrior postmen.

Dirty horse-hooves clopped on the bare sand as the two men departed.

"Thank you again for your help, Mr. Jacob. We appreciate what you have done. Now come inside and we can talk."

The king plodded towards the grand hut, and I had to slow my pace so as not to get ahead of him.

"Bayete," rang the cheers to the king as he and I entered.

My heart warmed up. It now seemed possible my wishes could one day be granted.

"Sit down, young man." Lobengula pointed to that beaten-earth bench that I'd sat on when I came with Fairburn on that first visit.

After taking his seat on his high chair, the king opened his mouth to address the court. "I have decided that Mr. Jacob be allowed to stay permanently in Bulawayo if he so wishes." Lobengula looked at his nobles with his intimidating eyes. "And pursuant to that, I am prepared to offer him a grant of land."

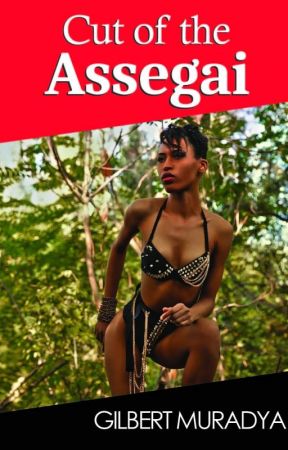

YOU ARE READING

Cut Of The Assegai

RandomA fabulous tale of romance and adventure set during the last years of King Lobengula's rule. Cut of the Assegai chronicles the life and struggles of an English teacher and his two female students whom he is in love with, at a fictional school in Old...