The first time I laid eyes on Lester Crowe he was rolling on the floor of his cell at the Hernando County Sheriff's Department, left eye swollen almost completely shut and blood pouring from his nose and mouth. His laughter shook the concrete walls.

I found out later why Crowe looked the way he did: his original cellmate hadn't taken kindly to Crowe's suggestion that his harelip resembled a certain part of the female anatomy. At the time, I didn't really understand how much he deserved to be lying on that floor, blood spattered on the front of his crisp orange jumper, or the importance of the events which had put him there. But I would soon enough.

Lester Crowe was my newest client.

Seven days before, I'd read about Mr. Crowe's arrest in the Coles Creek Sentinel, our local newspaper: Drifter arrested for young girl's murder. "Drifter" is newspaper-speak for "vagrant" or "criminal". Read a word like that and you immediately form an opinion about the person involved. You don't mean to; it just happens. That ability—the ability to make snap judgments based on limited information—is coded somewhere deep in our DNA and has been refined over millions of years. A word, a look, the cut of a person's hair—even things we don't consciously notice, like facial symmetry—can trigger it. This isn't particularly troublesome for law-abiding citizens, but for those accused of a crime, it's a nightmare. I'll admit the court system, at least in my little corner of Mississippi, does a pretty decent job of upholding the whole innocent-until-proven-guilty thing. The court of public opinion, well, that's another ballgame.

And Lester Crowe was already losing.

Although I wasn't his attorney yet, I still cringed when I read the headline. I knew Mr. Crowe would be charged with First-Degree Murder and the case would likely go to trial. No one wins when that happens, even if the defendant is ultimately convicted.

The victim is dead and they're never coming back.

A family has been shattered.

Killings often foster a sense of helplessness within the community. The world's goin' to hell, people say, scratching their heads. This ain't how it's supposed to be.

By the time the case made it to trial, it would be nearly impossible to find twelve jurors who could reasonably be viewed as impartial—the case was too high profile. Crowe's mug shot didn't do him any favors either; his thin frame and disheveled hair sold the Sentinel's vagrant angle far better than their article ever could. I knew every attorney in town—many I called friends—and didn't wish the burdensome task of representing him to fall on any of them.

It wasn't like this was something that happened often, either. We only had one or two murders a year in Hernando County. Every so often a drug dealer would get robbed and killed or a bar fight would get out of hand. It's easier for people to disregard killings like those. They had it coming, right? Not so lucky this time. This one involved someone's daughter. And when a little girl dies, the gloves go on.

The victim was fifteen-year-old Amanda Dunbar. She was an All-American girl by any standard: a straight-A student, a member of the Coles Creek High cross-country team, and captain of the cheerleading squad. The newspaper article described her as a "fun" and "outgoing" athlete, well-loved by students and teachers alike. What else do you say about a high-school student like Amanda? That she liked to sneak off to Lake Baldwin with her boyfriend late at night? That she experimented with pot and pills on the weekends? Of course not. Still, I'd learn both of those little tidbits about Amanda soon enough. She certainly wasn't the picture of perfection the paper made her out to be. Are any of us the same person inside as we present to the world?

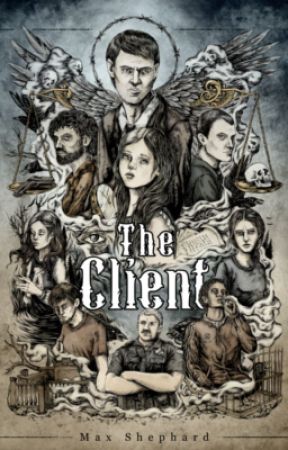

YOU ARE READING

The Client

ParanormalJack Price, a small-town public defender living in Coles Creek, Mississippi, gets more than he bargains for when he's appointed to represent Lester Crowe, a mysterious drifter charged with the murder of local high school girl Amanda Dunbar. Jack so...