The backlash from Judge Evans's dismissal of Lester's case was mighty and swift. The Sentinel's headline read: Judge dismisses case against alleged murderer. The picture that accompanied the article was stunning. The photographer's camera, trained on Lester's face to catch his reaction to the judge's ruling, had inadvertently captured the moment just before the rock—which had been thrown from behind the photographer—connected with Lester's left temple. Out of focus and frozen in time, the rock hung in midair, halfway between the person who'd thrown it and its target, as Lester's arms rose to protect his face. A great picture, really; a classic that would undoubtedly hang in the Sentinel's office for some time.

The article was a scathing takedown of the justice system in Mississippi. A pot smoker caught with a joint looks at jail time, but a murderer gets off with nothing? What kind of world are we living in? They'd conveniently failed to mention the case would be presented to the grand jury for indictment regardless of the dismissal. They'd covered many cases in Judge Evans's court and knew the truth well enough, but the truth doesn't sell papers. Drama does.

The article finally said what the others had only alluded to. What type of monster is Jack Price? Doesn't he care about his daughter? Couldn't he have withdrawn and let someone else handle it? Now a murderer is walking free!

When I was in sixth grade, there was a boy in my class who showed up the first day of school wearing neon orange socks. We wore uniforms every day, a consequence of our private elementary school's strict dress-code, but for some reason we could wear any color socks we wanted. In a sea of primary-colored khakis, polos, and jumpers, his socks may as well have been homing beacons for bullies. When he started wearing them all the time, some kids in our class singled him out and began harassing him. Just because he was a little bit different. Because people who didn't wear white socks were weird.

One day, I showed up to school wearing neon purple socks. I was tired of seeing him picked on and I figured if two people were wearing different-colored socks, maybe he wouldn't stand out so much and the bullies would leave him alone. So much for wishful thinking. Nothing changed—except that there were two weirdos to pick on now. After only two days I decided I'd had enough. On the third day, I showed up in regular white socks. After a while, as bullies often do, they moved on to harassing someone else. And I made a new friend out of the deal.

On the Friday morning after Lester's preliminary hearing, I felt like I was wearing neon purple socks again, but there would be no taking them off this time.

Judge Evans got it the worst, though. The article reported that dismissing a murder case at such an early stage was simply unprecedented. It certainly hadn't happened in the ten or so years I'd been practicing law in Coles Creek. Judge Evans's biggest problem: he didn't have an attorney. Magistrates in Mississippi don't have to have law degrees because they only deal with offenses that carry six months or less in the county jail. I've never really understood that line of reasoning. Public policy arguments aside, the practical outcome was Judge Evans didn't have the luxury of screwing up on such a large scale. And he paid for it dearly. He was vilified by the paper, the public, and most notably, by the District Attorney's office. The comments section for the paper's online version of the article had to be disabled after one anonymous commenter suggested Judge Evans should be taken out to Lake Baldwin and drowned. Paul Maxwell, the District Attorney, was quoted as saying, "That's a head scratcher right there. I'm not sure I've ever seen anything like that." What he said behind closed doors, I heard, was far worse. Considering his longstanding feud with Judge Evans, no one was surprised.

Evans would be the last of his kind. During the next election cycle his opponent, who did have a law degree, would focus almost exclusively on his decision in the Crowe case, reminding voters at every turn just what a fool Evans must be. He'd been on the bench too long; he was getting too old; he had let a murderer free. He buried the incumbent in a landslide, ending Judge Evans' almost twenty-five years on the bench.

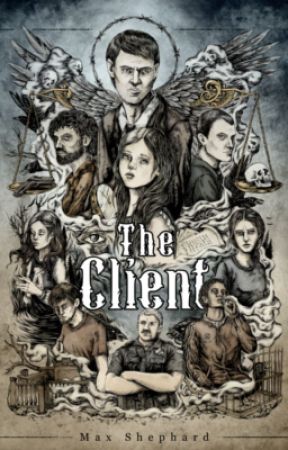

YOU ARE READING

The Client

ParanormalJack Price, a small-town public defender living in Coles Creek, Mississippi, gets more than he bargains for when he's appointed to represent Lester Crowe, a mysterious drifter charged with the murder of local high school girl Amanda Dunbar. Jack so...