It was a year after the artist was drowned that the loan exhibition of Hugo Blake's paintings was opened in Philadelphia by Maeve. "Whom the gods love die young," people said.

To remember those paintings is like remembering a dream-life spent with the Ever-living in an Ireland unmarred by men.

Except once, he never painted a human face or any form of life, human or fairy, yet the very light and air of them thrilled with life—it was as though he had painted life itself. There was the great 'Sliav Gullion" –stony, austere—the naked mountain against the northern sky, and to look at it was to be filled with a young, fierce hunger for heroic deeds, with the might of Cuchulain and Fionn. There was 'Loch Corrib' like a mirage from the first day of creation—there was Una's 'Dawn'...

The critics, inarticulate with wonder, seemed to sputter nonsensical reviews: "Blake paints as a seer," "He paints on the astral plane."

At the end of the room, alone on the grey wall, hung the "Portrait of Roisin Dhu". Before her, men and women stood worshiping, the old with tears, the young with fire in their eyes. There were some that it sent home.

Had Blake seen, anywhere on Earth, others were asking, that heart-breaking, entrancing face? Knowledge of the secrets of God was in the eyes; on the lips was the memory, the endurance and foreknowledge of endless pain; yet from the luminous, serene face shone out a beauty that made one crave for the spaces beyond death.

No woman in the world, we said, had been Hugo's Roisin Dhu; no mortal face had troubled him when he painted that immortal dream—that ecstasy beyond fear, that splendor beyond anguish—that wild, sweet holiness for which men die.

Maeve, as we knew, had been his old friend. When strangers clamored, "Was there a woman?" she would not tell. But one evening, when we five only were around Una's fire, she told us the strange, incredible tale.

"I will not tell everyone for a while," she said, "because so few would understand, and Hugo, unless one understood to the heights and depths, might seem to have been... Unkind. But I will tell you: There was a girl."

"It's almost impossible to believe," Liam said; "It's not a human body he has painted; nor even a human soul!"

"That is true in a way," Maeve answered, hesitating; "I will try to make you understand.

He was the loneliest being I have ever known. He was a little atom of misery and rebellion when my godmother rescued him in France. She bought the child from a starving drunkard who was near death. His mother, you know, was Nora Raftery, the actress; she ran away from her husband with Francois Raoul, taking the child, and died. Poor Blake rode over a precipice while hunting—mad with grief, and the boy was left without a friend in the world. It was I who taught him to read and write: already, he could draw.

To the end, he was the same passionate, lonely child. The anguish of pity and love he had for his mother he gave to her country when he came home: he suffered unbearable 'heim-weh' all the years he was studying abroad. The 'Dark Tower' as we called it, of our godmother's house on Loch Corrib was the place he loved best.

I have known no one who lived in such extremes, always, of misery or of joy. In any medium but paint he was helpless—chaotic or dumb, yet I think that his pictures came to him first not visually at all, but as intense perceptions of a mood. And between that moment of perception and the moment when it took form and color in his mind, he used to be like a wild creature in pain. He would prowl day and night around the region he meant to paint, waiting in a rage of impatience for the right moment of light and shadow to come, the incarnation of the soul... Then when he found it, the blessed mood of contentment would come and he would paint, day after day, until it was done. At those times, in the evenings, he would be exhausted and friendly, and much akin to a grateful child.

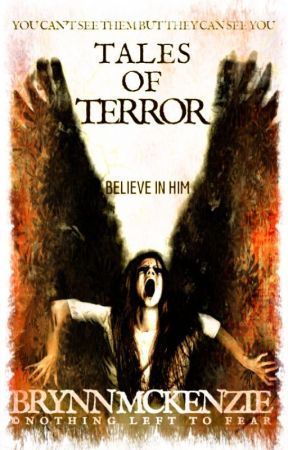

YOU ARE READING

TALES OF TERROR

NouvellesTALES OF TERROR *CreepyPastas *Urban Legends *Ghost Stories