It was typical of my dad to want to stop and offer the man a lift and just as typical of my mum to want to drive on. In the back seat, I said, 'Don't stop, Dad.' But it was already too late. Just fifteen seconds had passed since we saw the hitchhiker and already we were slowing down. I'd told him not to stop. But I'd no sooner said it than we did.

The rain was coming down harder now and it was very dark so I couldn't see very much of the man. He seemed quite large, towering over the car. He had long hair, hanging down over his eyes.

My father pressed the button that lowered the window. 'Where are you gong?' he asked.

'Ipswich.'

Ipswich was about twenty miles away. My mother didn't say anything. I could tell she was uncomfortable.

'You were heading there on foot?' my father asked.

'My car's broken down.'

'Well - we're heading that way. We can give you a lift.'

'John...'

My mother spoke my father's name quietly but already it was too late. The damage was done.

'Thanks,' the man said. He opened the back door. I suppose I'd better explain. The A12 is a long, dark, anonymous road that often goes through empty countryside with no buildings in sight. It was like that where we were now. There were no street lights. Pulled in on the hard shoulder, we must have been practically invisible to the other traffic rushing past. It was the one place in the world where you'd have to be crazy to pick up a stranger.

Because, you see, everyone knows about Fairfields. It's a big, ugly building not far from Woodbridge, surrounded by a wall that's fifteen metres high with spikes along the top and metal gates that open electrically. The name is quite new. It used to be called the East Suffolk Maximum Security Prison for the Criminally Insane. And right now we were only about ten miles away from it.

That's the point I'm trying to make. When you're ten miles away from a lunatic asylum, you don't stop in the dark to pick up someone you've never met. You have to say to yourself that maybe, just maybe, there could have been a break-out that night. Maybe one of the loonies has cut the throat of the guard at the gate and slipped out into the night. And so it doesn't matter if it's raining. It doesn't even matter if the local nuclear power station at Sizewell has just blown up and it's coming down radioactive slush. You just don't stop.

If you noticed, there is a reason for why my parents were slightly depressed, even on this day. That reason was my brother, Eddie. Nine years ago he fell into the path of a train; I was standing behind him, and had to watch him be crushed. But perhaps soon he will be but a memory, and we can continue our lives.

The back door slammed shut. The man eased himself into the back seat, rain water glistening on his jacket. The car drove forward again. I looked at him, trying to make out his features in the half light. He had a long face with a square chin and small, narrow eyes. His skin was pale, as if he hadn't been outdoors in a while. His hair was somewhere between brown and grey, hanging down in clumps. His clothes looked old and second-hand. A sports jacket and baggy corduroys. The sort of clothes a gardener might wear. His fingers were unusually long.

One hand was resting on his thigh and his fingers reached all the way to his knee. 'Have you been out for the day?' he asked. 'Yes.' My father knew he had annoyed my mother and he was determined to be cheerful and chatty, to show that he wasn't ashamed of what he'd done. 'We've been in Southwold. It's a beautiful place.' 'Oh yes.' He glanced at me and I saw that he had a scar running over his eye. It began on his forehead and ended on his cheek and it seemed to have pushed the eye a little to one side. It wasn't quite level with the other one. 'Do you know Southwold?' my father asked. 'No.'

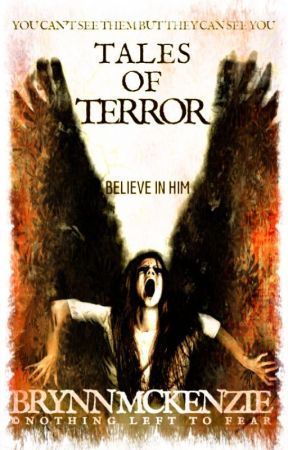

YOU ARE READING

TALES OF TERROR

Historia CortaTALES OF TERROR *CreepyPastas *Urban Legends *Ghost Stories